The Star Trek Problem: Why We Can't See Our AI Future

People love to talk about how progressive the original Star Trek was. And they’re right to. Consider, for example, Lieutenant Uhura on the bridge of the Enterprise – a Black woman in a position of authority on prime-time television in 1966. It was genuinely groundbreaking.

But they often forget (or don’t mention) that she was still wearing a minidress. And her job was basically answering the space telephone.

Star Trek’s creators could extrapolate in one dimension: a future of increasing racial equality. They imagined a world where skin color wouldn’t determine your career trajectory. That took genuine vision.

What they couldn’t see was the intersecting dimension of gender roles. They brought Uhura to the bridge but couldn’t imagine her doing anything other than what women were “supposed” to do in 1966. The future they envisioned was radical on one axis and completely conventional on another.

This is what I call “lazy extrapolation.” You take one visible trend, imagine everything else stays constant, draw a straight line forward, and call it foresight.

Aldous Huxley did the same thing in Brave New World. He was a genius at extrapolating social engineering – how society might deliberately remake human nature. But when he imagined a futuristic elevator, his vision of progress was of a being genetically engineered specifically for the task of pulling the levers.

He could imagine the remaking of humanity itself, but he couldn’t conceive of the electronics revolution – that a button and a circuit would make the operator’s job obsolete entirely.

This isn’t a criticism of these visionaries.

It’s an observation about the fundamental limits of human foresight. Because we’re all doing this, all the time. There’s a good chance you’re doing it in your business or career right now, which we’ll get to in a minute. The only question is whether we’re aware of it and what to do about it.

When Everyone “Sees” the Same Thing (And They’re All Wrong)

This timeless flaw is running rampant right now, driving the AI hype cycle. We’re drowning in one-dimensional extrapolations. Extrapolations are fine on their own, but when people mistake them as predictions, they create widespread panic or paralysis (or both).

And it’s impossible to make confident predictions about AI. To see why, let’s look at one of the most common claims: that AI will replace creatives and put knowledge workers out of a job.

The extrapolation goes like this… AI can generate content – text, images, code – quickly and efficiently. Therefore, it will replace all writers, designers, and programmers. Draw the line forward, and creative professionals are obsolete. So are knowledge workers.

But this misses two critical layers of how change actually unfolds.

First, it ignores second and third-order implications.

This is the Budding Effect in action. It’s named after Edward Budding who invented the mechanical lawnmower way back in 1830.

Before Budding’s invention, keeping grass short required a scythe-wielding gardener – expensive, labor-intensive, and imprecise. His mechanical mower, inspired by machines that trimmed cloth, made it suddenly feasible to maintain large, flat, perfectly manicured fields.

The immediate effect was obvious: lawn care became easier and cheaper (and some gardeners lost their jobs). But no one would have thought that the invention would ultimately give rise to a multi-billion dollar sports industry.

It did though. Because manicured playing fields enabled lawn sports like football and cricket to grow in popularity. And ultimately, it allowed organized athletics to grow at scale. In 1830, there was no direct line from “a better way to cut grass” to the NFL. That’s the point of the Budding Effect. Opportunities emerge when technology shifts. But they emerge in places we never thought to look, often solving problems we didn’t know we’d have.

The same pattern applies to AI and creative work. Yes, AI can generate content quickly. But what second-order effects does that create? When content becomes infinitely abundant and cheap, what becomes scarce? Human judgment, taste, curation, and trust. The bottleneck shifts from production to selection and curation.

Nobody hiring writers today is thinking, “If only I had more words.” They’re thinking, “How can I reach and serve my audience? What stories resonate with them, and how do I share those stories effectively?” AI doesn’t solve that problem. But it can make it worse by flooding the market with more options to sift through.

The creative professional who understands this isn’t competing on volume. They’re positioning themselves as the curator, the trusted guide, the one who knows what to make and what to ignore. So accurate prediction requires moving beyond the immediate effects. But that’s just the beginning.

Second, the “AI will replace creatives” ignores intersecting trends.

Even if you map those second and third-order effects perfectly, you’re still extrapolating in one dimension. The real complexity emerges when multiple trends collide.

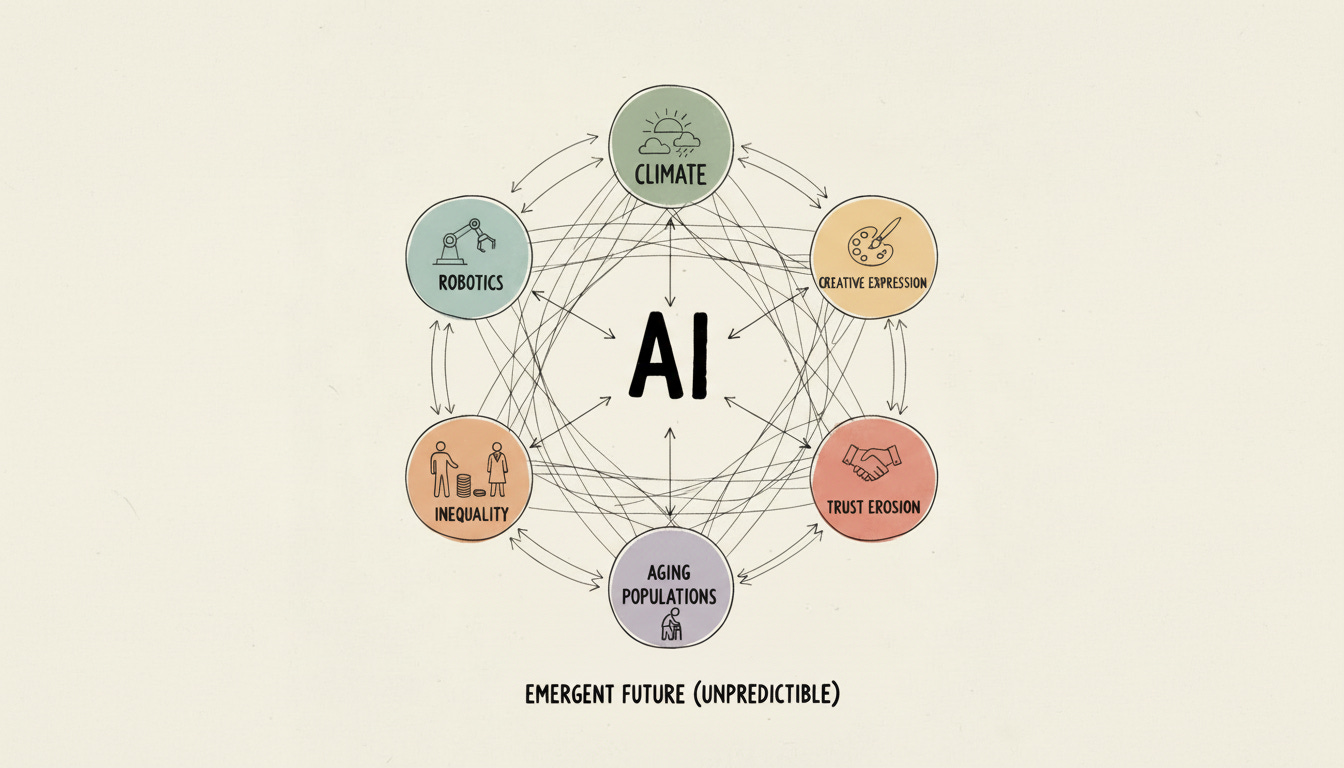

AI isn’t unfolding in a vacuum. It’s intersecting with robotics, nanotech, energy constraints, climate pressure, growing financial inequality, experiments with Universal Basic Income, political swings, aging populations in developed countries, and dozens of other massive trends.

Each intersection creates emergent effects that no trend would produce alone.

For example, let’s take the writer example from above even deeper. Understanding that people don’t hire writers just for words is a start. But that’s still thinking about writers as service providers in a market.

What happens when AI-generated content intersects with our fundamental human need for creative expression and validation? People don’t write only because someone will pay them. They write to contribute, to create, to be recognized for original work. That goes way beyond market dynamics. Now we’re talking about existential needs.

When AI absorbs much of the creative space, when your work competes not just with other humans but with infinite machine-generated alternatives, what happens to the human drive to create? What happens when one of humanity’s core identity-forming activities – making things – becomes something anyone can do instantly by typing a prompt?

Or consider how AI intersects with growing distrust. When anyone can generate professional-looking content, how do you know which voice to listen to? Trusted voices with proven track records become the only signal above the noise. And simultaneously, it’s even harder to build trust if you don’t already have a platform.

And what happens when AI creativity tools intersect with financial inequality? If everyone can produce professional-quality work instantly, does that democratize opportunity or just shift the gatekeeping to those who can afford the distribution and attention?

Like Star Trek imagining racial equality but missing gender roles, we might see AI’s impact on creative production while completely missing how it combines with identity, trust, meaning, and economic access to reshape not just the market for creative work but our relationship to creation itself.

And that’s just examining creative professionals through a few dimensions. There are dozens more we can’t even perceive yet.

In the Land of the Blind...

There’s an old saying:

“In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.”

This is the entrepreneur’s job. Our value is created by seeing something partially before the rest of the market sees it at all. This partial sight is the source of a big advantage.

Someone sees a trend early – maybe it’s that online events are about to explode, or that a certain market is underserved, or that a particular platform is going to dominate. They build their entire business around that insight. They create programs, build an audience, establish themselves as a voice in that space.

And it works. For a while, being early is enough. They have the conviction to act while others are still skeptical. They build momentum while the market is still underserved.

That single clear insight gives them direction and conviction. It helps them to move while others are standing still.

But here’s where it gets tricky.

There’s a difference between seeing one dimension clearly and assuming that’s the only dimension that matters. Between having conviction about a trend and believing you understand all its implications.

For example, when ChatGPT launched, there was an immediate race to use it for content generation. Flood the market with AI-written articles, social posts, newsletters. The thinking was simple: if you could produce 10x more content than your competitors, you’d dominate.

These entrepreneurs weren’t wrong about the trend. AI absolutely can generate content quickly. They had their “one eye” on something real. But they were extrapolating in only one dimension: production capacity.

What they missed were the intersecting dimensions. If everyone can produce 10x more content, then content itself becomes worthless. The bottleneck shifts from production to curation. Being able to generate more actually becomes a liability when everyone else can too.

But that’s just one intersection. What does content abundance do to trust? What happens to brand equity when the barrier to “looking professional” drops to zero? When anyone can produce polished content instantly, what distinguishes you?

I’m not arguing these questions have clear answers. Or that using AI to create more content is necessarily good or bad. The point is that most people racing to implement AI aren’t asking these questions at all. They’re extrapolating in one dimension (production capacity) while the real complexity lives in the intersections.

And that’s one danger of being that one-eyed king. You can see one dimension clearly but miss the intersections.

Another issue is that it’s deeply disconcerting to be the king if you know full well that you’re still half-blind. The very thing that gives you your edge is a constant, humbling reminder of how much you cannot see.

You know you’re not seeing the full picture. You know there are dimensions you’re missing, like Star Trek missed gender roles or Huxley missed electronics. You know your straight-line extrapolation is probably wrong in ways you can’t even conceive of yet.

And yet you have to act anyway. You have to commit resources, make bets, move forward with incomplete information.

That tension never goes away. In fact, it gets worse.

The Curse of (Slightly) More Awareness

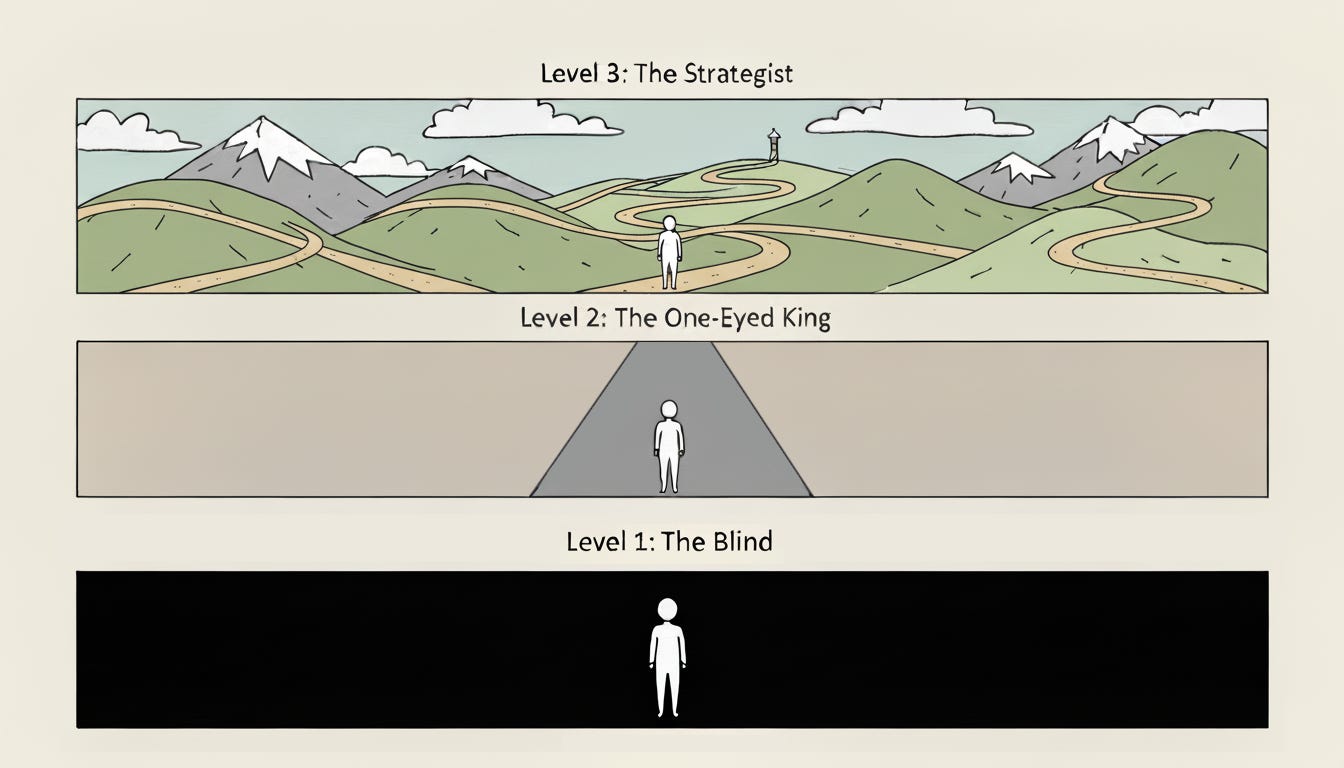

We can map this entrepreneurial journey up a ladder of awareness.

Level 1: The Blind

This is the market. Most people at this level operate purely in the present, reacting to what is. They don’t think about the future at all. They just wake up every day and deal with whatever’s in front of them.

Picture a marketing consultant in 2015. She’s built a solid practice doing SEO, content marketing, and email campaigns. She has a repeatable process, steady clients, predictable revenue. When someone mentions “influencer marketing” or “Instagram ads,” she nods politely but doesn’t take it seriously. That’s not real marketing. That’s just kids on their phones.

She’s not being stubborn. She’s executing on the model she knows. But she’s not asking, “What if consumer attention shifts entirely to mobile? What if my entire strategy becomes obsolete?”

It works fine in stable environments. But when the ground shifts – when the proven model stops working – she has no framework for understanding what’s changing or why. She’s optimized entirely for execution, which means she’s blindsided by disruption.

Level 2: The One-Eyed King

This is the driven entrepreneur. You see one powerful trend – “the future is online courses!” or “everyone’s going to need cybersecurity!” – and you build a world around it.

Imagine our marketing consultant four years later as Instagram and TikTok began picking up even more momentum. She sees that they’re not just fads but where attention is moving. So she doesn’t dabble. She goes all-in. She rebuilds her entire practice around short-form video and influencer partnerships.

Her old colleagues are still debating whether “social media marketing” is sustainable. She’s already teaching it. She has frameworks, case studies, and a waitlist of clients who want what she’s figured out.

This level is defined by high conviction, clarity, and massive focused action. She’s not paralyzed by complexity because she’s not seeing the complexity yet. She’s seeing one clear path forward, and she’s sprinting down it.

And it works. She builds authority, momentum, a profitable practice. She’s the one-eyed king. Until she starts seeing more.

Level 3: The Strategist

This is what happens after a decade or more of experience. You no longer see one trend. You see five. You see contradictions and complexity instead of clear black-and-white situations.

Our marketing consultant now knows that short-form video drives engagement, but she also knows it’s training audiences to have zero attention span for the deeper work her clients actually need. She knows building an audience on TikTok can help her clients get tons of attention, but the platform could also ban their account tomorrow because of an algorithm glitch. She knows AI tools can help create content faster, but they’re also flooding the market with so much mediocrity that cutting through the noise is harder than ever.

Instead of looking at the immediate impact, she considers the second and third-order effects. She starts asking different questions. Not “What’s going to happen?” but “What else might change?” Not “What trend can I jump on?” but “What other trends are intersecting with this one?”

When a client asks, “Should we bet on AI-generated content?” she can’t give them the clean answer she used to be able to give. Because she sees that AI might make content production irrelevant, or it might make human curation more valuable, or both, depending on how consumer trust and platform algorithms evolve.

These are better questions. Smarter questions. But they’re also paralyzing questions.

Because now every insight comes with a counter-insight. Every trend has a counter-trend. She can see that social media gives you reach, but it’s also training your audience to expect everything for free. She can see that automation creates efficiency, but it also commoditizes the service she’s selling.

And suddenly she’s not operating from conviction anymore – she’s operating from sophisticated uncertainty. She’s too experienced to chase the simple story. But the complex reality doesn’t offer a clear path forward. So she finds herself stuck in analysis, endlessly mapping terrain, hesitating to commit.

Her sophistication becomes her prison.

This reveals the great paradox of leadership: the higher you climb, the less confident you become.

Not because you’re losing your edge, but because you’re gaining perspective. You’re seeing more. And the more you see, the more you realize how much you don’t see.

As you climb the ladder, you’re developing the very skill that makes decisive action harder: the ability to see how many ways you could be wrong.

Resisting Premature Certainty

The solution isn’t to become a better prophet. It’s not to try and “see with both eyes.” That’s an arrogant fantasy. The real answer is learning to resist premature certainty. To stop grabbing the first, loudest, simplest story – like the AI hype cycle – and instead hold the tension of not knowing for as long as possible.

Most entrepreneurs pride themselves on decisiveness. On making a call and moving on. But there’s a difference between decisiveness and premature certainty. And the payoff comes from changing your core question from “What’s the right prediction?” to “How long can I sit with this complexity until the real signal emerges from the noise?”

That’s harder than it sounds. Because sitting with ambiguity and acting without certainty requires a different kind of courage. (And it’s something I’ll cover in my next essay.)

But it’s the only way to avoid the trap of lazy extrapolation while still moving forward.

In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. But the one-eyed man who knows he’s half-blind? That’s wisdom.

Hey, before you go...if this essay resonated, would you hit the like (heart) button or leave a quick comment? It really helps the publication grow and lets me know what’s connecting. Thanks in advance - I really appreciate it! :-)

This is sort of a nitpick, but also kind of an expansion of your point...

The original 1965 Star Trek pilot (the one where the captain was Pike rather than Kirk) had a woman executive officer, "Number One". But the network executives insisted Roddenberry get rid of her, so he folded her character traits (being highly logical) into Spock and made him the second-in-command instead. (The pilot version of Spock doesn't act especially stoic or unemotional - he's pretty much just a guy with pointy ears.) Also, women crewmembers wore trousers in the pilot, and baggy rather than form-fitting tops.

So even when you have the rare visionary who does see things like this, popular opinion (or the people with money) are still probably not going to appreciate it. ;-)

Here's a picture of Pike and Number One (the woman in uniform on the right, who like the woman in uniform on the left, is wearing pants, not a skirt!): https://wherebadmovieslive.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/the-cage-star-trek-season-1-pilot.jpg

Brilliantly put, Danny.

I've been thinking that we are already in a technological singularity, but it's more than that, as economic and societal changes are also taking place.

What a wonderfully fascinating time to be playing on Earth!