The Most Important Business Skill (That Most People Have Never Even Heard Of)

You can get pretty far in business with the obvious skills. Good copywriting and sales. Financial literacy and planning. The ability to build systems and spot opportunities. But there’s one skill that pretty much trumps everything else. It amplifies all the other skills, and most entrepreneurs have never even heard of it.

It’s perspective taking.

The ability to accurately reconstruct how someone else is seeing, feeling, and understanding their situation. And it uses what they say, what they don’t say, and everything surrounding the conversation – while maintaining enough distance to stay clear-headed about what you’re observing.

When you develop this skill, something shifts across your entire business. Your sales conversations stop feeling like combat and start creating genuine alignment. Your leadership becomes more effective because you understand what your team is actually navigating, not just what they’re telling you on the surface. Your partnerships become more resilient because you surface the mismatched assumptions before they calcify into resentment.

The entrepreneurs who master this operate in a completely different reality than their competitors. They see what’s actually happening, instead of projecting what they hope is happening. But to understand why this skill matters so much, we first need to understand why it’s so hard.

Why This Feels So Unnatural

Most of us think we’re already good at this. We confuse perspective taking with being “nice” or “empathetic.” We assume that because we care about people, we understand them. But caring and understanding are different animals entirely.

For example, if your team is stressed about a deadline and you empathize so deeply that you absorb their stress, you haven’t actually helped. You’ve added more anxiety to the room. You’re drowning right alongside them.

Perspective taking is different. Instead of feeling their emotion, the goal is to reconstruct their internal world – their beliefs, their constraints, their history, what they’re actually trying to optimize for in this moment.

And humans are terrible at this by default.

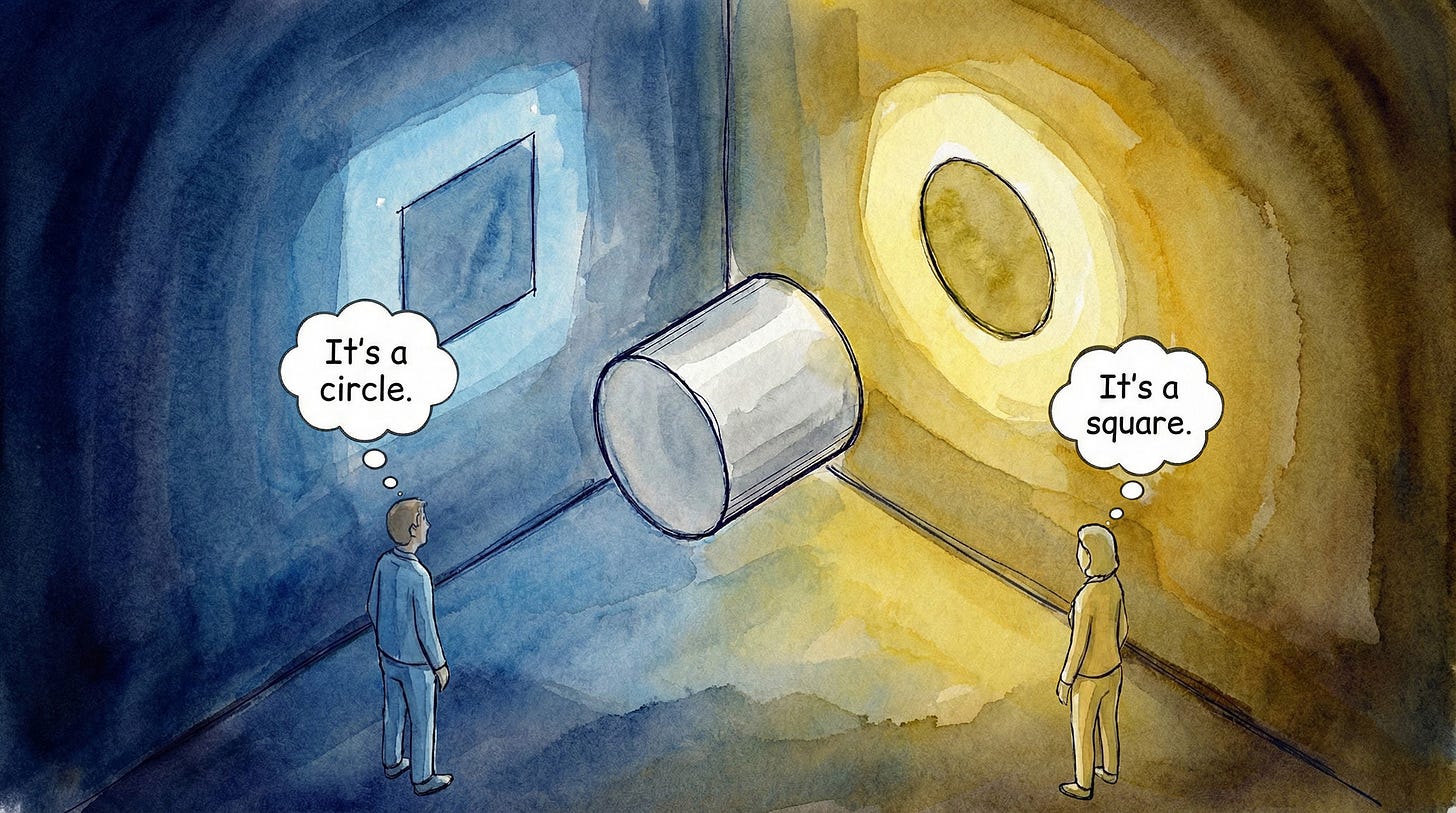

We’re wired to assume that other people see, know, and value roughly the same things we do. When we look at a problem, we think we’re seeing objective reality. But we’re really just seeing our slice of it, filtered through our experience and blind spots.

So when someone disagrees with our strategy, our brain doesn’t naturally wonder what they’re seeing that we’re missing. Instead, it asks why they’re being difficult.

When a client hesitates at our offer, we don’t instinctively explore their constraints and fears. We assume they don’t see the value. Or when a team member seems disengaged, we interpret it through our own lens… they must not care, they must be overwhelmed, they must be the wrong fit. We rarely pause to consider that they might be operating from completely different information or assumptions than we are.

Overriding this default takes real effort. You have to suppress your own ego, suspend your own judgment, and see through someone else’s filters. Because this is so difficult – and so rare – it creates a massive edge for the people who actually do it.

How to Model Before You Move

People usually approach difficult conversations backwards.

They focus on what to say. They rehearse their pitch, prepare their talking points, and worry about finding the right words. They think the problem is tactical. If they frame this correctly, the other person will understand. But all those communication tactics fail if your internal model of the other person is wrong.

You can have perfect mirroring technique, impeccable body language, and a beautifully crafted value proposition. But if you think someone is motivated by money when they’re actually motivated by recognition, everything you say will miss.

You can validate their feelings all day long, but if you’re validating the wrong feeling – if they’re actually anxious but you’re responding to what you think is skepticism – you’re not building trust. You’re creating confusion.

Ultimately, you cannot be guided by a perspective you do not hold.

You cannot coach, sell, partner with, support, or lead someone if you’re fundamentally misunderstanding how they’re experiencing the situation. And the sequence matters. First, build an accurate model of what’s happening for them – their fears, their constraints, their unseen motivations, their actual decision-making criteria. Only then do you choose your words and actions.

And when a conversation doesn’t land – when someone pulls back, when alignment fractures, when you walk away feeling like you missed something – there are two distinct ways it can break down

Seeing Wrong vs. Speaking Wrong

Understanding the difference in these two failure points is critical because they require completely different fixes.

Sometimes you’re seeing wrong. You’ve built the wrong model of what’s happening for the other person.

You assume you know what someone means without actually checking. They say “I’m stuck,” and you immediately map that to your own experience of being stuck. But their stuck might be completely different from yours.

Or you project your own thinking onto them – assuming they’d value what you value, risk what you’d risk, or prioritize what you’d prioritize. Or you get so tangled in their emotion that you lose the clarity you need to help. They’re anxious, so you become anxious. They’re defensive, so you get defensive.

Sometimes you lock into a narrative too early because you think you’ve seen this pattern before. You stop exploring right when you need to keep gathering data.

All of these are lens problems. You’re seeing incorrectly. And when your lens is wrong, nothing else matters.

Other times you’re speaking wrong. Your understanding is actually sound, and you’ve built an accurate model of what’s happening. However, the way you express or act on that understanding creates friction.

Maybe you go too deep, too fast. You see something true about them – perhaps you recognize a pattern they haven’t admitted to themselves yet – and you name it before they’re ready. The insight is accurate, but the timing destroys trust.

Or your delivery doesn’t match their preferred level of abstraction. You’re speaking in strategic vision when they need concrete next steps. You’re offering tactical details when they need to feel inspired first. The content is right, but the translation is wrong.

These are execution problems, not perception problems.

Now, most entrepreneurs think they have language problems when they actually have lens problems.

They think, “I need better words, a better script, a better way to frame this.” So they keep polishing their language, refining their pitch, trying new tactics.

But they never fix the fundamental issue. They’re seeing the situation incorrectly.

Think of it like wearing glasses. If the world looks blurry, you can try polishing the glass. You can wipe it harder and harder. But if you picked up the wrong prescription, no amount of polishing will fix the image.

This is why “fix the lens before the language” matters. You can’t solve a perception problem with better communication. You have to go upstream. You have to learn to see differently.

Channeling Your Inner Cartographer

So, how do you actually do this? You first have to stop thinking of yourself as a debater, trying to win an argument, or a performer, trying to impress an audience.

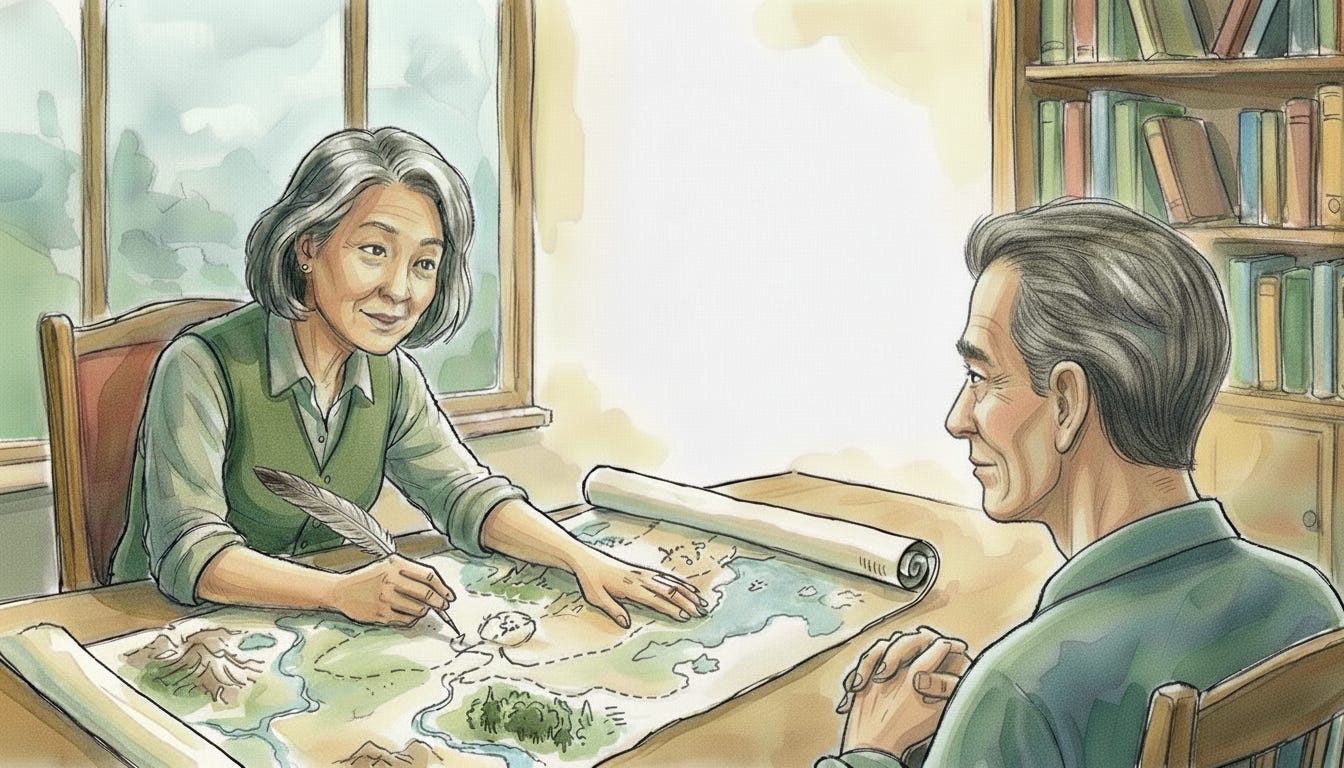

Think of yourself as a cartographer.

Your job is not to transform the other person’s mind. Your job is to map it. It’s like you’re standing on the edge of an unknown continent – another human being’s internal world. You can’t see it directly. So you use sonar.

You send out a pulse – a question, a hypothesis, a tentative observation – and you wait for the echo.

Pulse: “It sounds like the timeline is the biggest stressor here?”

Echo: “Well, the timeline is tight, but honestly, I’m just not sure the team has the bandwidth to handle the change management right now.”

That’s a signal. The obstacle isn’t time – it’s capacity. Now you know something you didn’t know 30 seconds ago.

And often, the most important information isn’t in what people say, it’s in what they don’t say.

Consider a coaching client who says, “Right now I’ve got a few people I’m mentoring.” The average listener hears “they have clients.”

The cartographer hears the specific word choice, “mentoring,” and infers what isn’t being said. They aren’t calling them “clients.” They likely aren’t charging them. They are testing an identity they haven’t fully claimed yet. That can change the entire conversation.

You stop getting frustrated by “difficult” behaviors. You stop taking resistance personally. Instead, resistance becomes data. If someone gives you an objection, that’s not an attack or a rejection. It’s a feature of the terrain you haven’t noticed yet.

The key is that you’re not judging the terrain. You’re mapping it. And when your map is accurate, people start saying things like “I’ve never felt so understood” or “How did you know that?”

Not because you’re psychic. Because you built an accurate model before you tried to move.

Three High-Stakes Shifts

When you start to incorporate perspective taking into your business, it will transform outcomes across many different contexts. Here are three examples.

The Sales Call

The traditional sales model is combat: you vs. them. The prospect tosses out an objection (”It’s too expensive”), and you’re trained to parry (”Compared to what?”). They put up their shields, waiting for you to trick them.

Perspective taking creates alignment.

When a prospect says, “I need to talk to my spouse,” the combatant tries to isolate the objection. “Are you going to let someone else stop your dreams?”

The cartographer asks what model of the world makes that statement true. Maybe they value partnership over autonomy. Maybe they’ve made bad financial decisions before and promised they wouldn’t do it again.

So you align. “That makes total sense. When you talk to them, what specific worries do you think they’ll have? Let’s make sure you have answers so you don’t feel caught off guard.”

Suddenly, you aren’t fighting them from an opposing side. You’re equipping them. You’re sitting on the same side of the table, looking at the problem together. And when prospects feel equipped instead of pressured, they convert differently. They show up more committed, they implement better, and they refer others because the relationship started from alignment, not manipulation.

Leadership and Management

We often attribute malice or laziness to our teams when the reality is a missing map.

You give clear instructions. The team member nods. Two weeks later, the project is wrong. The default reaction is that they didn’t listen or aren’t capable.

The cartographer asks what perspective they were holding that made this output seem right. Usually you’ll find a constraint you didn’t see. Maybe they thought “fast” mattered more than “right” because of something you said three months ago. Maybe they were waiting for stakeholder input they didn’t feel safe asking for.

When you map their constraints, you fix the system, not just the project. Your team starts operating with less friction and fewer surprises. They feel safer surfacing problems early, which means you’re solving real issues before they compound instead of playing whack-a-mole with symptoms.

Conflict Resolution

Most conflicts come from unspoken and incompatible assumptions.

Take a common tension – a “micromanager” and a “rogue.” The micromanager thinks the rogue is reckless. The rogue thinks the micromanager is a dinosaur. If you mediate by asking them to “respect each other,” you’ll fail. You have to map the perspectives.

Ask the micromanager what they’re seeing that makes them need to step in. The answer usually isn’t power – it’s fear. They’re worried that a lack of standardization will crash the system as you scale.

Ask the rogue what they’re seeing that makes them ignore the process. You might find that they value speed. They believe the current process is too slow to meet client needs.

Once you uncover those assumptions, you can get to the real issue. They’re debating stability versus speed. That’s a legitimate business tension, and once the map is clear, they can solve it together.

In all three cases, the shift to perspective taking changes what’s possible. You can create a greater impact without necessarily working harder. You just work from better data.

The Strategic Edge

Perspective taking isn’t a “soft skill” relegated to HR departments and team-building exercises. It’s one of the highest-leverage entrepreneurial meta-skills you can develop.

And the encouraging part is that it’s trainable. Most people never develop it because they’ve never been taught that it’s something to develop. They think you’re either naturally good at reading people or you’re not. They treat it like charisma or charm – an innate trait, not a learned capability.

But that’s wrong. Perspective taking is a skill stack. And when you start working on it deliberately, even small improvements compound quickly.

When you take someone else’s perspective, you close deals that would have slipped away. You align teams that would have stayed stuck. You build partnerships that actually work. Not because you got better at talking, but because you got better at seeing.

The entrepreneurs who master this operate in a different reality. The difference isn’t more information. The difference is better perception. They see what’s actually there, not what they hope is there. And in a world where almost everyone is projecting, assuming, and reacting, the person who can actually see has an enormous advantage.

So in your next important conversation – a sales call, a leadership discussion, a difficult talk with your co-founder – pause before you act. Ask yourself what you’re assuming about how they’re seeing this situation. Then ask them a question designed to test that assumption, not confirm it.

Listen for what’s not being said as much as what is. Notice the gaps, the hesitations, the careful phrasing. And before you offer any solution or next step, ask yourself whether you actually understand their world well enough to guide them through it.

Because you can’t navigate a terrain you haven’t mapped. And no amount of eloquence can compensate for being lost.

Hey, before you go...if this essay resonated, would you hit the like (heart) button or leave a quick comment? It really helps the publication grow and lets me know what’s connecting. Thanks in advance - I really appreciate it! :-)

Thanks, Danny! This is incredibly insightful. I'll have to read it a few times more for it to sink in fully.

Many smiles and much metta.

perspective taking ... brilliant and spot on!